The true

fencing outfit, including mask, fencing jacket and glove came in to common use

during the mid-nineteenth century, and was not regulated until after the

inaugural Olympics of 1896, where international competitions began to demand

uniformity in both costume and rules (rules continued to be disputed among the

fencing countries, instigating the formation of the FIE, the International

Fencing Federation, in 1913). Throughout the century various colors and styles

were allowed, particularly for the women who at that time did not participate

in competitions. The outfit changed along with the fashions of the times as

well.

|

| Paraphernalia of Fencing from 1911 Encyclopedia of Sport and Games |

At the

beginning of the 19th century there was not much of a fencing

uniform. Even the mask, conceived by the fencing master La Boessiere in 1780,

was not commonly worn, still considered ungentlemanly and showing a lack of

skill. Certain customs were adopted to protect the face, such as the point of

the foil being kept low and withholding the riposte after a parry until the

opponent had time to recover. Images from manuals probably accurately portrayed

the outfits worn, everyday clothes and a cravat or “gros mouchoir” to protect

the neck.

|

| Watercolor of Henry Angelo's Fencing Academy, by Rowlandson, 1787 |

|

| from the 1829 London Encyclopedia |

The early

masks were solid metal with openings for the eyes and tied around the head.

|

| Early fencing Equipment from the Diderot Encyclopedia |

By 1822 the

fencing outfit has become a bit more standardized. The artists George and

Robert Cruickshank depict a fencing match at the rooms in St. James Street. The

fencers wear a wire mesh mask that covers the face and short high collared

white jackets that button up on the side. The masks do not have any bib. The

fencers wear slippers or sandals on their feet. Some of the jackets in the

background have color to them. It is difficult to tell if they wear gloves, but

DeBast in 1836 recommends a padded glove that also protects the wrist but does

not restrict it, and that the inside of the glove must very flexible.

|

| Cruikshank's picture of fencing on St. James Street in 1822 |

In Maclaren’s

System of Fencing published in 1864

he recommends that

“All exposed parts of the body be thoroughly protected. The head and the face by a strong, hand-wrought wire mask. The neck and the breast by a stout leather jacket reaching from the chin to a few inches below the waist, with a well-fitting collar buttoning (behind) around the neck. The lower part of the body by a leather flap or apron, either attached to the jacket or buckled round the waist. The right hand by a soft and pliable leather glove or gauntlet, well padded on the back.”The apron is not seen very often, probably used more often with sabre or broadsword.

Keep in mind

most of the outfit was probably custom made. Sporting equipment sellers of the

later 19th century show masks, foils and gloves for sale, as well as

a plastrons.

The jacket,

often of canvas or some stiff material, would button on the side opposite the

sword arm and was trim and waist-length. Jackets might be of leather for the

practice or singlestick or sabre. Pictures of fencers often display a wide belt

to denote the limit of the target area.

|

| From an article in Frank Leslies Monthly called "Fencers and the Art of Fencing" 1893 |

The Fencing Mask

The fencing

mask evolved from a solid piece of iron covering the face to a mesh of strong

wire. Ear protectors were later added, as well as a simple bib. By the late 19th

century a full bib completed the mask.

From H. A.

Colmore Dunn’s book Fencing from 1889

“This should be made of good stout wire, and should always be carefully inspected before use, to see that none of the links are loose or failing, as the point of a foil has been known to find its way through the space occupied by a single link. See that the flaps are large enough to cover the ears properly, and also that the top bar across the front of the mask does not interfere with the sight.”

|

| FOIL MASKS |

The Fencing

Jacket

These were generally

made of a stout canvas or leather, or a combination of the two. It would button

up on the side of the jacket away from the sword arm (hence right and left

handed jackets would be different).

Dunn

recommends that

“It is best to have the jacket made of a material which, without being too heavy, is sufficiently stiff to offer some resistance in the event of a foil breaking. Some kind of canvas seems to combine these advantages as well as anything, and, for the purposes of foil-play, is to be preferred to leather, which does better to deaden the force of a cut in stick-play than to keep out a sharp point. Take particular care that the jacket is made high in the collar, so as to protect the throat by leaving no space uncovered between it and the mask. The neglect of this precaution may lead to serious accidents, and also tends to spoil the attitude, as, if the bare throat is exposed to attack, the head is involuntarily thrust forward to protect the gap, and the result is that a cramped position is acquired, which is exceedingly difficult to cure."

George Chapman”s

Foil Practice published in 1861 adds

that the fencing-master should also wear a well-padded plastron or leather

cuirass [chest protector], upon which the pupil during his lesson directs his

foil.

|

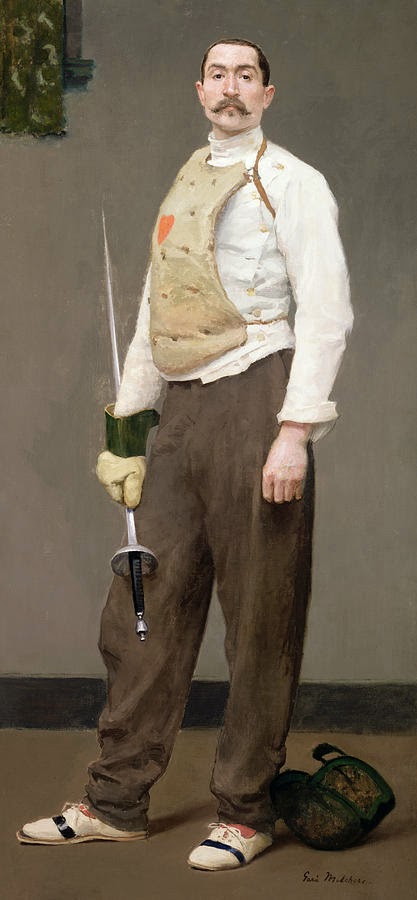

| The Fencing Master by Julius Gari Melchers C. 1900 wearing a plastron with a heart |

The required

white uniform of today was by no means a rule in the nineteenth century. White

was common, because it was easiest for the judges to see hits with the point of

the foil, but there are many examples of various colored jackets. Black was not

the sole property of the fencing master, and there did not seem to be any

conventions concerning this. Black uniforms were used in epee contests when the

chalk marks were used as a scoring device.

The black uniform

went in and out of favor as this attempt at scoring was debated. Breck’s

article in the Outing Magazine of 1895 congratulates an improvement in

the AFLA rules that eliminates the use of chalk as a marker for scoring.

“The new laws are a vast improvement over those of last year. In the first place, the use of chalked foil-points has been abolished. To enable the four judges to see touches more easily, white jackets are required to be worn instead of the hitherto customary suits of solemn black.”

Breck still

laments some of the rules and the uniform requirements that were unique to

America. In the United States the target area was limited to the upper inside

quarter of the jacket. Often jackets would have a line or extra patch of

material to designate the target.

“It is a matter for regret that the median line rule has been retained. In France and Italy a touch counts, as it obviously should, on either side of the body. The collegians compromised by counting all touches on the right of a line drawn down the middle of the left breast, which is certainly better than the A. F. L. A. rule, the object of which is presumably to encourage accuracy. Some such provision was necessary ten years ago, but fencing in America is no longer in its swaddling clothes. There are many fencers in Paris who make a practice of placing their points on their opponents' left sides.”

|

| Note V. Z. Post's split color jacket denoting the foil target area |

Finally, in

1892 Rondelle’s Foil and Sabre: A Grammar of Fencing merely indicates that

“The two costumes should be of the same color and of a strong material to avoid

accidents.”

The heart on

the breast of the fencing jacket was an affectation occasionally used,

sometimes by the instructor, less frequently on the fencer, though Thomas

Stephens mentions it in his New System of

Broad and Small Sword Exercise from 1843. “An easy dress should be worn,

and it is usual, in academies, to have a spot or heart on the left side of the

breast of the waistcoat.”

Fencing Pants &

Knickers

Trousers or

pantaloons were worn by men, the color of jacket and pants generally being

white or black, though this was not a rule. Pants worn followed the fashion of

the time. Knee Breeches or knickers were commonly worn by men in the 18th

century. Full length trousers came in to fashion in the early 19th

century as part of everyday wardrobe for men, and this is often part of the

fencing costume of the period Knee breeches remained associated with sporting

activities such as horseback riding, golf and fencing.

|

| Egerton Castle wearing black fencing knee breeches or knickers |

Though not

commonly seen, Castellote’s Handbook of

Fencing in 1882 adds:

“That a

leather thigh-pad is also a necessary precaution, especially when your

opponent’s play is unknown to you, and you have to run the risk of its being

violent or irregular.”

Many period

images show a wide belt being worn. According to the Squires 1890 Catalogue of Sportsman Supplies out of

New York, the fencing belt was made of red leather, three inches wide,

fancy-stitched, and kid-lined. The catalogue also notes that the belt “gives

strength and staying power”.

The fencing

rules of the amateur Athletic Union of the United States published in the

Spalding Athletic Guide of 1891 that in foil contests a fencing belt not

exceeding four inches in width should be worn. The belt delineates the lower

part of the target area in many rules.

%2BFencing%2BMaster.jpg) |

| Example of the Fencing Belt - Painting by Tancrede Bastet 1890 |

Fencing Gloves

Gloves did

not seem to be used until fencing became more of a sport or exercise. A glove

with a gauntlet would be worn on the hand handling the foil. There are pictures

of two types. One appears to be more of a training glove, thickly padded with a

leather gauntlet. The other was usually of a softer leather that enabled better

manipulation for the fingers. Dunn explains the necessity of the touch of the

fingers in fencing

“The selection of a glove is by no means a matter of indifference, and it is difficult to get a good one in this country. It should be just sufliciently padded to save the hand, but subject to that it should be light and flexible, so as to interfere as little as possible with the play of wrist and fingers. Most English-made gloves are exceedingly faulty in this respect, being cumbrous and shapeless, with no distinction in the length of the fingers. The padding should be properly distributed, so as to protect the parts most exposed, and particularly the tip of the thumb, which otherwise is apt to be jarred, the grasp of the foil being thereby impaired. The fingers of the glove should be well-shaped, following the configuration of the hand, so as to allow easy and independent movement. To secure ample space for the wrist, it is well to have a certain fullness at the point where the hand joins the gauntlet. To this end it is better, as in the illustration, not to cut the gauntlet straight, but to scollop a piece out of it, to be filled by the softer material of the glove, so as to give scope for the bend of the wrist. The palm should be roomy, so as to avoid cramping the thumb. If the hand is boxed up tightly in a stiff case, there is no chance of fencing neatly and lightly, as you must be sensitive to the slightest variations in the amount of pressure offered by your opponent to your blade, if you are to detect and anticipate any change in his tactics to which this pressure may be the prelude. This power of judging by the touch, which may be compared to the faculty of “hands” in horsemanship, is one of the most valuable qualities in fencing; but there is this point in the analogy in favour of the latter—that in fencing, this quality, called by the French masters “le sentiment du fer,” can, in a measure, be acquired by practice, whilst -in the case of the former it appears to be more in the nature of a fairy gift.”

|

| Leather Fencing Glove |

|

| Padded Fencing Glove |

|

| Fencing Gauntlet |

Fencing Shoes

One of the

more curious parts of the outfit was the fencing shoe. An inquiry on this

subject to Malcolm Fare of the National Fencing Museum in London revealed the

unique nature and evolution of this apparel. He reports that:

“These days the thought of wearing a fencing shoe with a flap at the end does seem very strange, yet they were used for some 250 years. The open-toed fencing sandal for the leading foot was first depicted by De La Touche in Les vrays principes de l’espée seule, 1670. Believed to provide greater freedom of movement than an enclosed shoe, it had a sole projecting 2-3 inches beyond the toes. By the 18th century both sandals and shoes were available with a projecting flap, which was used to make a resonant sound, the appel*, during the salute.De Bast's Manuel D’Escrime, 1836, described fencing sandals as a kind of slipper, the right one being open at the end so as to give the toes freedom of movement, with the sole, which had an added layer of felt, extending some way.George Chapman in The Art of Fencing, 1864, says “The shoes should be of leather for the ‘uppers’ and of stout buff for the soles. The sole of the right shoe is frequently made with a padded flap to protect the toes from inconvenience in the fall of the foot; this addition to the shoe is not, however, of necessity.”

*According to Viguier’s Vocabulaire D’Escrime, 1910, appels were also used in a lesson to ensure that a pupil had good balance. During a bout they served to accentuate feints and false attacks as well as distracting the opponent. They were used to intimidate and undermine, making it possible to gain distance and execute compound hits.

That was the theory. In practice, the flap gradually shortened during the 19th century so that by the turn of the 20th century it barely projected more than a quarter of an inch, yet was recognisably different from the shoe worn on the other foot.”

Castellote

added in 1882 that if practicing outdoors you should wear light shoes with

spikes, but on boarded floors the shoes should be made of soft leather for the

top part and a stout buff for the soles.

The

Consolidate Library Volume of 1907 adds that “Ordinary, rubber-soled tennis

shoes are often worn by amateur fencers, but the regulation French fencing

shoes, which have broad, leather soles are the best. The principal requirement

is that the shoes shall not slip.”

Women’s Fencing Outfit

|

| "L'escrimeuse" by French Impressionist painter Jean Beraud |

Women’s

fencing outfits were not as strictly regulated since they practiced solely for

exercise, not having formal competitions until 1912.

In a 1902

article in Lady’s Realm magazine the women’s outfit at the London Ladies

Fencing Club is described.

“The club uniform consists of a short silk lined black alpaca skirt with the regulation brass-buttoned white linen fencing coat. The skirts are cut somewhat after the fashion of the cycling skirt, and most of the members wear black or white shoes. The stockings are either of silk or wool: the silken hose is distinctly to be recommended for daintiness and finish. A white glove with a black or scarlet gauntlet is drawn over the right hand.One very skilful and graceful woman fencer deprecates—as does Lady Colin Campbell—the wearing of a skirt. She is assured by long practice that full knickerbockers of black satin or vicuna allow unfettered and more graceful play for the limbs.”

|

| From the Badminton Magazine article "the Art of Modern Fencing" 1907 |

Manriques Foil Fencing Manual of 1920 gives the

additional advice that

“from a medical standpoint, it is best to protect the chest by wrapping strips of cloth across it and under the arms to form a bandage to guard against any possible bruise from being struck there with the foil button; about three yards of cheese cloth or similar material crossed and recrossed until a firm solid bandage is made as suggested.”

Fashion

influenced the New York upper class ladies who fenced. They would dress in

lavish elegant outfits of silk blouses designed by select tailors to cause

interest among the society newspapers, who might publish sketches of the

outfits. The colors and styles would be of a wide variety.

An article

from Harper’s Bazaar in 1900 informs us that “Much latitude is observed

in the costumes of the women who fence. While the majority wear padded linen

jackets, many wear shirt-waists of any color or material to suit their taste.

“Fussy” waists, however, are tabooed, and any sensible woman will recognize at

once the objection – the trial to the spirit of the fencing teacher, who must

be continually dodging about with his foil to avoid catching it in flowing lace

or ruffles or bows.”

|

| Examples of more fanciful ladies outfits, paintings by Joseph Arnad Koppay |

The Fencing Sword, or

Foil

The fencing

Foil, was made of steel, four sided and tapering to a point that was flattened

out in to a small round disc called the button. The button was “usually covered

with parchment or some other material to prevents damage to the opponent’s

jacket and ribs” according to the instructions of Every Boy’s Book of Sport and Pastime edited by Professor Hoffman

in 1897

|

| From "Fencing" by Breck in 1915 |

Dunn

describes the blade, as quadrangular, and about thirty-three or thirty-four

inches long,

“The remaining part of the foil, tapering down from the hilt to the end, which is clenched by the “pummel,” made of steel or the like, is covered by a wooden frame called the “grip.” It is of the utmost importance that the grip should be of a good shape, following the formation of the hand when rightly placed. A straight grip, such as is occasionally met with, does not afford nearly such a comfortable, firm hold as one that is fairly arched, and fits in naturally with the curve of the thumb. It should also be of a good length, say five inches, so as to allow ample space for the hand, as, if too short, it is sure to contract and tire the muscles. Another advantage of a long grip is that, on occasion, it enables you, by slightly shifting the hand down towards the pummel, to deceive your opponent in his calculation of the extent of your reach. A fair sized pummel, say an inch and a half to two inches long, serves to balance the foil and make it come up well in the hand.”

Chapman in 1861

says

“The best foil blades are manufactured at Solingen, and those numbered 5 are mostly made use of. Open guards of iron, slightly bent upwards, or towards the point, for the better protection of the thumb, are generally used in fencing, and are more convenient than close ones. Twisted twine is the best covering for the handles, which are made of different sizes, slightly curved and more or less squared or flattened. The handle should in no case be rounded, nor should it be too much tapered towards the pummel; it should be of nearly uniform size throughout. Lastly, the pummel should not be over large, and only sufficiently weighty to balance the blade when placed on the forefinger, between two and three inches from the guard."

Both Chapman

and Castellote tell us that a piece of gutta percha tied neatly over the

blunted end or button of the foil will answer to prevent accidents in lunging.

A hard and durable rubber or latex, gutta-percha was also used to make jewelry,

grips for pistols, furniture and golf balls until other cheaper materials

became easily available.

And the

Consolidated Library of 1907 says that in selecting foils

“choose a pair that seem to be of the right weight for your strength; it will be best for the beginner to learn with very light weapons. See that each balances, when held with the blade supported by the finger an inch from the hilt. If not provided with good-sized metal buttons, the point of the foil should be wound with good, strong, waxed cord, so as to form a button nearly half an inch in diameter; this is a desirable precaution even when metal buttons are provided. The handle should be curved, and bound with twine.”

|

Parts of the Foil from theManuel pour l'étude des règles de l'Escrime au Fleuret et à l'Espadon published in 1860 |

Some fencing catalogues: Henry C. Squires from 1890 and John Piggott, Ltd. from 1905

Finally, here

are some examples of fencing outfits from the1899 publication Escrimeurs Contemporains by Henry de

Gourdourville. The book features photographs and information on contemporary

fencers.