Archibald Maclaren was an instructor of physical

education and fencing. In 1864 he produced a manual on fencing for military

instructors. In 1868 it was combine with his Military System of Gymnastic

Exercises, with some updates. The 1868 edition was printed in London under the

superintendence of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. The General Order for Horse

Guards stated:

“The Field Marshal Commanding-in-Chief has directed

the following Regulations for the Gymnastic and Fencing Instruction, and for

the Club Exercise, to be printed and bound together in one volume, as more

convenient for reference and use than the three separate books hitherto

published. By Command, Wm. PAULET, A.G.”

He produced the instructional manual during a

period where there was concern that the British military physical fitness was

not up to standard. The British Army was keen to open schools of physical

training as a result of the Crimean War, where, as Major Frederick Hammersley

said “the general health and fitness of recruits and soldiers left a good deal

to be desired.”

The first part of the manual, comprising a large

portion, is dedicated to the gymnastic exercises. It includes a variety of

exercises covering such activities as dumb bells, bar bells, vaulting horse,

rings, free climbing and escalading (the surmounting of a wall or other

obstacle too elevated to be surmounted by a leap or a vault). Maclaren says of

the exercises that “Every exercise comprised in the present system has been

selected for its value in one of two aspects: the first, or elementary aspect,

being the manner and degree in which it tends to cultivate the physical

resources of the body by increasing its dexterity and rapidity of action, its

strength in overcoming resistance, and its power of enduring protracted

fatigue; while the second, or practical aspect, is the manner and degree in

which its practice may be brought to aid directly in the professional duties of

the soldier”.

A System of Fencing

Maclaren’s system should be noted for its attempt

at efficiency (4 parries, rather than 8), while also giving an in depth

analysis of how and why the actions are to be made. He studied fencing in

France, presumably the source for most of his material. As it is a system for

the military, the lessons are presented for instructors to use in individual or

group lessons. The manual is laid out with an introduction and explanation for

each action, followed by instructions on how to teach the action.

Maclaren begins by defining fencing, and indicates

that the foil is taught because he considers the thrust to be the most

effective way of disabling an opponent. The movements of fencing can be

arranged under four heads:

-Preliminary Movements or Positions

-Defensive Movements or Parries

-Offensive Movements or Attacks

-Return Attacks

PART I - Preliminary Movements

and Positions

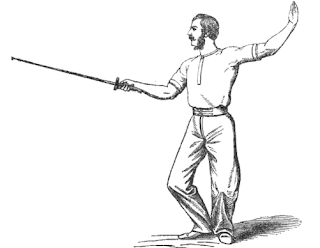

This details the movements to come on guard,

starting from a position of attention and finishing in the guard.

He emphasizes that “Too much care cannot be

bestowed upon the acquisition of a correct guard, for on this depends

much of the force and accuracy of the movements in attack

and defence.”

He notes that the power of the lunge comes from

straightening of the left leg, and that the left hand should fall in position

to within a few inches of the thigh. Maclaren concludes that the concentrated

action of all the different parts of the body renders the

sword-thrust so deadly.

|

| Coming On Guard |

It is interesting to note that his instructions for

the “longe” (lunge) were altered from his original 1864 publication. In the

1864 publication of a “System of Fencing” he instructs that in the lunge “The

column of the body is not now, as in the guard, held perpendicular to

the centre of the span of the lower limbs; it has

partaken of their forward action, and by its fall has added to their

momentum”.

By 1868 he has changed this to keeping the upright

position, which was common in the French method. This may have occurred

following criticism from other sources, including Richard Burton (Burton notes

in his “Sword Exercise”: Mr. MacLaren, in his ' System of

Fencing,' &c. sensibly advocates "resting the

weight of the body equally upon both legs." He also lowers the

right hand in the Lunge, and he throws the trunk forward, perhaps

with a little exaggeration. Other than this criticism, though, Burton was an

ardent supporter of Maclaren and preferred his gym to that of Angelo’s.)

|

| On the Word "Thrust" |

|

| The Longe |

Finally with the guard, the advance and retreat,

the lunge and the recover, the “learner must be taught to execute them with

faultless precision and accuracy before any attempt is made to carry him into

the other divisions of the art.”

|

| Position of the Hand in the Longe |

PART II - Defensive Movements or Parries

Maclaren explains his teaching method for a group.

It is to single out one man to teach, and then repeat with each individual as

the others circle around to observe.

He gives an explanation of the lines. There are the

inner and outer lines, and the upper and under lines. These create four openings.

The parry is the special protection for each of the four openings. The

defensive motions are made from the engagement. These two movements are called

respectively the inner and outer engagements, or the

engagements of quarte and tierce. The hand stays in the central

position when pressing from the inside, and the hand turns when pressing from

the outside.

Maclaren notes that in the quarte parry the hand

need only pass a few inches to the inner line to make the defense, for as the

attack “passed farther and farther outwards; and, although at the

moment of its contact with the defending blade, it may have been made

to deviate from the true line but a small fraction of an inch, yet

when the longe is completed it will have passed a foot outside the most outlying

portion of the breast; just as a shot quitting the

muzzle of a gun, and deviating a hair's breadth from the straight

line, will be many yards from it at the end of its flight, and the

longer its flight the wider its deviation.”

|

| Parry of Quarte |

|

| Parry of Tierce |

The parries of seconde and semi-circle defend the

lower lines. In the semi-circle parry the point “sweeps on until it is as high

as the face, and the hand is elevated a few inches, not only to complete the

defence of the upper opening, but the more distinctly to expose the

breast of the adversary to the return thrust. This is the

Parry of Semicircle and is perhaps the most artistically formed, and

in all its features, the most effective parry in the series.”

|

| Parry of Seconde |

|

| Parry of Semicircle |

He adds that there is a second defense for each

line, that being the parries of Quinte, Sixte, Octave, and Prime. The object of

the second defense was to give variety in the defenses, but since the same

attack deceives both parries, it requires a double labor to learn. He also

notes (as Angelo says) that prime is a broadsword, not a smallsword parry.

Counter parries are protection against disengages.

His explanation offers an example of Maclaren’s detailed description:

“The instructor and learner are again in the

position of adversaries, with the blades joined on the inner line.

The instructor, extending his arm, advances his point above the learner's hand.

We have seen that quarte will guard this. But were the instructor to lower his

point during the extension, and thrust on the under division; or to pass a

little farther and thrust on the under line outside; or go still farther, and,

elevating the point, thrust above the hand outside, what then? As the attacking

blade sinks from the upper to the under line, eluding the

contact of the defending one as it completed its parry (quarte), the

latter has but to sweep on, while the arm remains stationary forming a central

point or pivot on which the hand and foil revolve, and, whether the assailing

blade terminate its attack on one of the under lines, or rise above

the hand on the outer line, the defending blade, if revolving with sufficient

rapidity, must overtake it; and as it comes up to the point from which it

started, completing its circle, will pass it off as if by its first and simple

parry.' This is called a Counter Parry, and there are

four of this description, corresponding to and receiving their names

from, the simple parries.”

PART III - Offensive Movements or Attacks.

Maclaren defines the target as limited to between

the waist and the collarbone, and extending from armpit to breastbone. On

special occasions it might be further reduced to a circle of a few

inches in diameter, marked on the center of this space, for the

practice of accuracy. He suggests the use of this target because, besides

developing accuracy, it is most likely to deliver a killing blow.

He divides attacks in to three Orders (Direct, Indirect,

and Counter Attacks), which are then subdivided in to Series. After each Series

are instructions on teaching the action.

For the First Order of Direct attacks, the First

Series is made Under the Blade, and should be made with opposition. As the

covering of one line in a defensive position exposes another, a disengagement

is required. Two consecutive disengagements is called the One Two. Three

separate consecutive disengagements is called the One Two Three, but is a

method falling in to disuse for its complexity.

The Second Series of instruction goes around the

blade, the Double to deceive the counter parry. Another example of the detail

Maclaren goes in to describe the action:

“Again instructor and learner stand in

front of each other, the blades joined on the inner line. The learner

makes the disengagement to the outer line which the instructor parries with

counter quarte. This formation of counter quarte on the disengagement

to the outer line leaves the blades respectively in the same position as before

the attack was made; but if, during the act of forming the counter quarte,

the attacking blade keeps the lead, and as the revolving blade on the defence

comes up on the outer line on its counter, neutralizing the first

disengagement, the attacking blade passes to the inner line, again dips and

again rises to the outer line, the original opening will be found. Thus

the second movement is actually a circle formed within the larger

circular defence, starting from and terminating at the opening outside above

the hand…As in the One Two Three and the Counter Counter, The more

complicated of these combinations are seldom made in the assault; but

in the lesson they may be accurately made, and should be assiduously practiced.”

The Third Series is over the blade. This is the cut

over. In addition you can make the cut over with the semi-double, and other attacks

may follow the cut over, such as the one two and the double.

Maclaren notes that the cut over is more effective

as a second attack than as a first. It is more easily and safely made when the

adversary's point is elevated than when it is level; or when his arm is much

drawn back.

Maclaren states that “combined attacks

in fencing are, on a small scale facsimiles of the

approaches made by a besieging force,—a series of zig-zags, getting

nearer and nearer at each move to the point assailed until the intervening

distance can be cleared in a final spring.”

The Second Order consists of Indirect Attacks. They

are made previous to a movement of menace or assault, to distract the

adversary’s attention, to disturb the security of his position, or to mislead

his judgement.

The First Series is the Changement. The Second Series

is the Double Engagement. The Third Series is the Beat, which drives the

opposing blade a sufficient distance to enable a thrust to reach the breast. The

Fourth Series is the beat reverse, an indirect attack that combines the

advantages of both changement and beat. The Fifth Series is the Absence,

relying on a sense of touch and anticipating a beat with the blades quit.

The sixth series is the Pressure, which consists of a

slight addition to the engagement, by bringing the point lower down on the

forte of the opposing blade; and although at the

disadvantage of foible to forte, pressing it out of the

line, until the opening desired be obtained.

The Third Order is Counter Attacks. Maclaren

describes these as an alternative to a defensive movement against an indirect

attack.

The First series is the Changement, which is a

movement called the Counter Disengagement. The Second Series is on the

Double Engagement. The same counter attacks may be made on the double

engagement. The Third Series is on the Beat, and the same counter attacks

may be made on the beat. If the counter attacker perceives the preparation of

the beat attack, they can advance their point with opposition, and the beat

will arrive too late or be delivered on the forte of the advancing blade and

therefore be insufficient. The Fourth Series is on the Beat Reverse, which

can be done on the counter disengagement. The Fifth Series is on the

Absence and the Sixth Series is on the Pressure.

PART IV. Return Attacks (the

Riposte).

Maclaren states that no parry should ever be formed

without its being followed up by a return. He also notes that the parry is

actually aided by the fullness of the attacker’s lunge, bringing the assailants

breast close to the point of the opposing blade. The defender can lunge on the

return if the adversary feels the attack parried and recovers, so Maclaren

recommends that both the return with a simple extension and return with the

lunge should be practiced. The returns are named after the parries from which

they are made. Thus the return after the parry of quarte is called

the Return in quarte; and that after the parry of tierce, the Return

in tierce, &c., &c.

After the First Series of simple returns, the Second

Series is the Returns Reverse to the outside line. The Third Series is Second

Returns, the Fourth Series is the Double Return, the Fifth Series is Double

Return Reverse, the

Sixth Series is The Return Cut-Over (This is most

effective when the adversary is on the recovery of the lunge.)

Another form of Second Attack can be made from the

lunge, if the adversary is careless in his return, or makes it too complicated,

the attacker can remain in the lunge and parry the return, giving a second

return. Maclaren notes that there is danger of exposure in lingering in the lunge,

but a smart fencer can use it to bait a trap. Maclaren provides lesson in this

with the straight thrust, the disengagement and the cut over.

Indirect Return Attacks are coupled with second

actions, such as the beat, the graze, bindings. So for instance the defender

would make a firm parry in quarte, then give a firm beat and deliver the

thrust.

Irregular Attacks

These are a series of return offensive

movements called time attacks, which are made during the adversary’s

attack, and not at its conclusion. These differ from counter attacks, inasmuch

as they are made on direct and not on indirect attacks of an

adversary. They can be practiced with an opponent advancing within distance, or

withdrawing their hand during the attack.

The Assault

Maclaren gives rules for the Assault. Initially the

Assault should be conducted under the supervision of the instructor, and limited

to selected movements. He notes that when fencing against different adversaries

“No two men fence absolutely alike; and movements that are found effective

against one adversary prove quite ineffective against others. All that an

instructor therefore should aim at is to teach the learner the nature and

purpose of the several movements as set down in his book of

instructions, and to qualify him to execute them with perfect precision and the

greatest possible quickness…the instructor can give him the hand, so

to speak, of the swordsman, the head he must provide for

himself.”

A few general rules for conducting the assault are

here added.

1. All exposed parts of the body to be

thoroughly protected. The head and face by a strong, hand-wrought wire mask.

The neck and breast by a stout leather jacket reaching from the chin to a few

inches below the waist, with a well-fitting collar buttoning (behind) around

the neck. The lower part of the body by a leather flap or apron,

either attached to the jacket or buckled round the waist. The right hand by a

soft and pliable leather glove or gauntlet, well padded on the back.

2. The adversaries to fall on guard beyond hitting

distance.

3. .When both adversaries longe at the

same time, and both hits are on the targets, to count for neither; if only one

hit be on the target, such hit to count.

4. When both adversaries thrust at the

same time, but one only with the longe, and both hits are on the target, to

count for the hit given on the longe.

5. It is perfectly fair to make a second attack on

the same longe, but if at the time of the second attack the adversary

gives a return thrust, and both hits are on the target, the return only to

count.

The Salute

Maclaren then describes the Salute in Quarte and

Tierce. It is “Performed on occasions or special encounters, or ‘Assaults of Arms’,

as they are called, for the double purpose of suppling and preparing

the fencer for the assault, and of showing in a graceful and

advantageous manner to spectators the chief movements and

positions of the art.”

The remainder of the fencing manual gives a listing

of the class lessons. This is followed by a short exercise for a bayonet

engaged with a bayonet. This is followed, for the last section, with a series

of exercises for the regulation clubs, applicable to all stations where dumb

and bar bells are not supplied.